General Physics and Synchrotron Radiation – Giorgio Margaritondo's research

We explore the history of physics in general, and in particular that of x-rays. A key objective is to eliminate misunderstandings and misconceptions that prevent a correct appreciation of fundamental science concepts and a realistic prospective of their historical development. We also propose very simple presentations of advanced and diversified science topics — such as synchrotron radiation, free electron lasers and tsunamis

Highlight:

Albert Einstein DID NOT derive the idea of photons from the photoelectric effect. This historical misconception is often presented to students, but it is plainly wrong: the necessary data did not exist at that time. Einstein derived the notion of photon from a very elegant theoretical analysis of the entropy of electromagnetic radiation. Then, he was incredibly bold in proposing the result – the existence of photons – as a real phenomenon rather than a mathematical artifact.

For in-depth discussions, see:

Dismantling myths about the history of science:

Myth No. 1: Atoms were universally accepted by scientists after the works of Lavoisier and Avogadro in the 18th and 19th centuries. Thus, they provided a solid foundation for statistical mechanics, Boltzmann’s atomistic explanation of thermodynamics. |

|

Reality: Atoms were NOT universally accepted until the early years of the 20th century. In the late 19th century, their existence was challenged since classical electromagnetism could not justify stable atoms. Boltzmann was viciously attacked for his theories and pushed to suicide in 1906. Paradoxically, the year before Einstein’s theory of Brownian motion had irreversibly demonstrated that atoms do exit.

Myth No. 2: The discovery of the Doppler effect in 1845, because of its fundamental and practical importance, made its author Christian Doppler famous and professionally successful. |

|

Reality: Doppler and his effect were viciously attacked with inquisition-like methods by an incompetent colleague, Petzval, and his accomplices. Incredibly, the members of the Austrian Academy of Sciences sided with Doppler’s enemies and voted to deny the existence of the Doppler effect. As a consequence, the university of Vienna disgracefully dismissed Doppler: he died shortly afterwards, in 1852, of tuberculosis in Venice. All these aspects are missing from many of Doppler’s biographies but were recently reported, very affectively, by David Nolte in Physics Today (Vol. 73, issue 3, page 30, 2020)

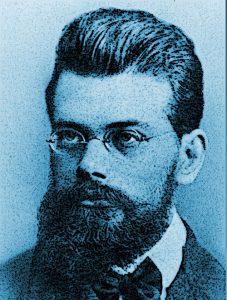

Giorgio Margaritondo, your host

(giorgio.margaritondo@epfl.ch)

A pleasant music box background (Chopin):